Lindsay Kyte’s refreshingly spare tale of North America’s first cooperative

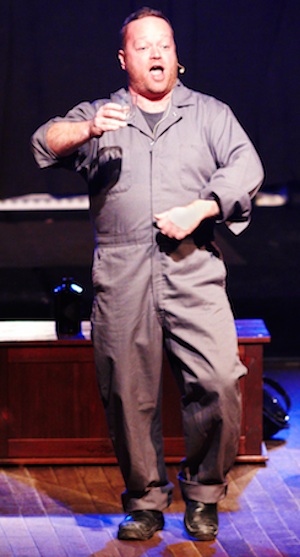

housing project – photo: Michael Halbwachs

BY ROD NICHOLLS

The performance of Tompkinsville (written by Lindsay Kyte and directed by Burgandy Code) at the Reserve Mines Fire Hall on Saturday night (April 25) was buoyed by the support of a large audience full of people who obviously still live, or have roots in the community celebrated in the play, including many who are related to the playwright. The audience and venue made this a very special night. But if you missed the show in Reserve Mines and have a chance to see it in Antigonish (April 30), Pictou (May 2) or Halifax (May 3) then don’t think twice. Go, because this is a well-crafted and entertaining piece of theatre to be enjoyed no matter where you’re from.

The story of North America’s first cooperative housing project could easily have inspired an earnest, plodding script larded with historical exposition and punctuated with wordy monologues. Not so, Tompkinsville. It stages a refreshingly spare tale. Though the play draws on ambitious themes – religion, economics, education, politics (including family politics) – it does so deftly, largely through dialogue, and it moves along with tremendous kinetic energy. Using five actors plus a musical narrator (Lindsay Kyte) and guitarist (Chris Corrigan), the seamless integration of music and acting is key to its theatrical success.

The rhythmic drive of some songs (music by Ian Sherwood, lyrics by Sherwood & Kyte) distinguishes them from the plaintiff folk style of others, and while Kyte’s voice does have the flavour of cross-over country, this is a long way from Nashville. But no matter how you define this eclectic “Tompkinsville sound,” it imparts a cohesive spirit and distinctive feel to the play. The narrator’s songs create emotionally compelling and meaningful scenic transitions; and in brief wordless segues, Chris Corrigan’s guitar riffs and cuts through the acting space, pushing dramatic momentum relentlessly. Nor does the audience relax to an entertaining “musical interlude when Dancin’ Archie Devison (Ryan Rogerson) sings,” because his songs are inseparable from his characteristic act of drinking.

Joe Laben (Jarrod MacLean) presents a challenging task for an actor. Just how can one convey the inhibitions that Archie’s fellow miner feels about his profound but untutored intelligence? Or the love of family that is extraordinary, yet seemingly so normal? At the outset, moreover, I found MacLean’s accent a bit off-putting. An attempt at Kraut-Caper fusion? Yet his patient, disciplined effort eventually won me over. A turning point was Joe’s address to the Council in Antigonish (requesting support for the housing cooperative) when he exploited the tried and true tactic of an ordinary man tossing aside a prepared script in order to speak spontaneously and honestly. Then, playing against expectation, Joe only speaks very briefly and MacLean delivers those few words with measured eloquence. His performance ends up working by exemplifying the “less is more” ethos that is part of Tompkinsville’s overall appeal.

To say that, is not to overlook the theatrically rich texture of the acting as a whole. Campbell plays the Mine Manager as well as Father Jimmy, and Tough plays Mary Arnold in addition to Kathy Ann Devison. This is no doubt determined by the economics of a touring show but was no aesthetic loss. Both actors switch back and forth in plain view, instantaneously and with only subtle adjustments to voice and demeanor. Throughout the play, stylized movement – sometimes representing whole actions and sometimes syncing perfectly with music in dramatic transitions – emerges from the dominant naturalism and reverts back to it, sinuously. Actors deliver a full range of sound effects (including wonderful colliery whistle) with simple props or their own voices. Despite performing in a musically alive and echo-friendly Fire Hall, it’s also worth noting that there was no problem with clarity and projection of the actors’ voices. Finally, the actors constantly rearrange numerous chairs to imaginatively create diverse settings.

Perhaps the only major flaw was the lack of risers which left audience members on the same level as the actors and hence unable to fully appreciate the blocking or gain a broad visual impression. Speaking of the audience, I couldn’t help noticing the lack of representation from the growing number of theatre groups in the area (Bandshell Players, Boardmore, Highland Arts, Savoy, for example). Hopefully, that changed on Sunday night. That’s not just because Tompskinsville resonates thematically with the local community. My point is different. Sometimes (less often than we’d like to think) community theatre does rise to a professional level. But an essential condition for making that a more regular occurrence is to participate in a shared, ongoing effort to develop critical terms of reference and identify benchmarks for evaluating what we do. I’m far from hyping Tompkinsville as some kind of Cape Breton Hamlet. To steal a phrase from someone who knew what she was talking about, however, it is certainly a highly theatrical and professionally accomplished piece of “indigenous Cape Breton theatre.” And it’s worth understanding why.