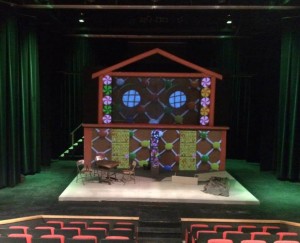

The set greeting audience members entering the Boardmore Playhouse looks more like something belonging to the fairy tale musical Into The Woods rather than an excoriating black comedy about the freedom of speech under an authoritarian regime.

The set greeting audience members entering the Boardmore Playhouse looks more like something belonging to the fairy tale musical Into The Woods rather than an excoriating black comedy about the freedom of speech under an authoritarian regime.

It looks like a giant ginger bread house with gumdrop decorations and candy cane trim and peppermints that slowly swirl. It’s a projected image, computer generated, that when the house lights dim, morphs into prison walls and barbed wire.

A writer, Katurian (Mike McPhee), with a day job in a slaughterhouse to support his care of his brain damaged brother, Michal (Aaron Corbett), faces two detectives: Tupolski (Gary Walsh), the seen it all veteran, and Ariel (Todd Hiscock), the thuggish younger cop. Katurian, defying audience expectations, practically grovels in servility before his interrogators; yes, his stories are dark, yes, his stories are about vicious physical harm inflicted on children, but they are just stories–he is no rebel, no dissenter, and disclaims any political content in his stories.

But real life children have been murdered in ways too similar to the gruesome goings on in Katurian’s tale to be ignored.

So begins The Pillowman, Irish playwright Martin McDonagh’s plunge into the deep waters of an artist’s responsibility for the stories he or she brings into the world. McDonagh must have had many conversations about this for his own work, like the high body count farce, Lieutenant of Inishmore written two years before Pillowman and staged this past November at the Highland Arts Centre [READ A REVIEW HERE], or In Bruges, the equally violent cult film with a strong Cape Breton fan base.

McDonagh’s conclusion is more pitiless in a way than his brutal police state: the artist, in the end, has one responsibility to the survival of his or her work; all else–politics, audience, family, self–fail and pass away. And I don’t know if I disagree with him. Or maybe I’m entirely wrong about there being a message at all.

Director Rod Nicholls, a philosophy professor, has the background to deal with what McDonagh brings to the surface with his play. His set is stylized but the actors’ performances are full of naturalistic nuance and emotion that grabs hold of the audience’s need to empathize. His A-List cast of local theatre favourites give some of the strongest performances of their careers. Nicolls made every element of this production serve McDonagh’s dark vision and created a professional level production.

Gary Walsh, almost grandfatherly in his performance, never let go of his character’s surface affability even when luxuriating in its most brutal side. His expertise with comedic timing brought the most laughs from the audience and with just a change in tone of voice, opened to the audience the unplumbable tragedy of this man’s life.

Todd Hiscock as the cocky, more violent of the brace of cops exuded an actual physical menace. The way his character fixedly gazed at McPhee’s cringing writer, how he prowled around behind him, had an animal quality, like a big cat coiled to pounce.

Rachel Murphy, Wayne McKay, Carrie MacDonald, Michael MacNeil, and Owen MacDonald all did excellent work as the various characters bringing Katurian’s characters to life, mostly through mime. Using movement with very little dialogue and working as a troupe, they gave each character its own identity and body language.

The large crew needs to be commended on bringing off a logistically difficult play without making their work obvious to the audience. When every detail is precise (like Ariel’s boxy leather jacket) to the point that’s the only way it seems it could be, then it’s proof of a professional level crew working with a very fine director.

This played last week, January 27 to February 1, but storm delays and other considerations kept me from attending until its second last performance. Otherwise I would gushing how everyone should go see it as one of the best productions the Cape Breton University drama group has ever mounted and how they have become innovators in set projection design. And I would have written the review as I have now: avoiding too much of a description of the action of the play. Like Katurian’s bleak fairie stories, it is an exquisitely told tale that should be enjoyed, not second hand in a review, but first hand on a stage in an equally excellent production like this one.

And I hope you have that opportunity someday.