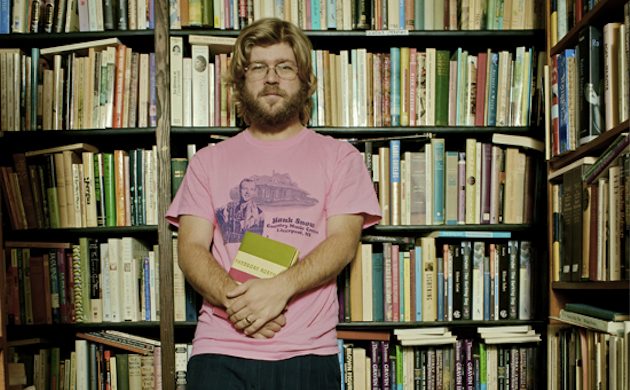

With the bright twang of banjo and lyrical stylings steeped in an earthy warmth and sincerity, the charm of Old Man Luedecke’s music is undeniable. It has a character that is at once nostalgic, yet firmly rooted in the immediacy of today. The Chester-based singer/songwriter is the headline act of the first show in the Granville Green concert series on July 4, fresh from the festivities of the Stan Rogers folk festival. Later on this month, he will perform again in Cape Breton, in the more intimate settings of Kiju’s at the Membertou Trade and Convention Centre on July 23 and at Mabou’s Red Shoe Pub on July 24. He will also be performing twice during the Celtic Colours International Festival in October.

Ever gracious, Luedecke took some time to shoot the breeze with What’s Goin On.

_____

WGO: You’re originally from Toronto. What was the draw for you to come to the East Coast?

OML: Well I just followed a girl here, really. And we’re still together, we met up in the Yukon, she came to NSCAD and I came with her.

WGO: Aside from romance, what is it about the East Coast that makes you stay?

OML: I had lived in a bunch of different cities when I was younger, and we found Halifax [first]. Then, I’ve lived in Chester for about five years now which is the longest I’ve lived anywhere, and I love it. My musical, performing life has always been based here. I bought a banjo about a year before I moved here, my first gigs were here, and I’ve written all my songs here. All my efforts–at becoming a performer and being someone who has traveled around playing music for a living–have been based here. I’ve made a life here fairly accidentally, but obviously I like it enough to stay.

WGO: About the more interpersonal aspect of your music – there’s this storytelling aspect of your performances that’s really strong. And that’s something that’s a fairly ancient tradition. What are your thoughts about that method in a modern context? Does it face challenges in a technologically mediated, individualistic culture?

OML: That’s a nice big question. I’m not quite sure how to answer! In terms of the storytelling though, I often feel that I don’t tell enough stories in my songs. But I guess for me, I try to write lyrics that you can go back to, and mull over. I guess with a lot of songs the lyrics are sort of accidental and abstract and I want more sense out of music than that. I guess if the song is good enough you find meaning in abstractions, for sure. But I guess for me, I’m interested in hearing things that are beautiful and make you think.

I guess I feel fundamentally that I can communicate with a song and that a song is a universe in itself and that I have a couple minutes to get something across that doesn’t need a whole lot else.

WGO: Are there specific places where you look for meaning in your music?

OML: It’s strange, I’m going through a period right now where I look at all the things I’ve said over the last little while. I’m examining all this stuff to see if it’s true–and I think it is–just in case it just ends up being a whole load of hooey.

The truth is, I’m often angry at the stories people tell. I mean, I love storytelling but I find that so many times [the stories] fall into these same molds that basically kind of remove agency from the teller. Like things are ‘meant to be’ or not meant to be…a lot of our traditional storytelling is not that based on the struggles that I find in my own life. I tend to search for meaning, I tend to want to make beautiful things out of a conscious struggle for betterment. I’m looking for a way to communicate this desire to grow without just being like ‘oh you know I was a bad man, and I gambled here and gambled there’.

I think I’m just trying to find a way to sing about this desire to become something, in a way that doesn’t turn people off as being goody-goody or as being sugarcoated, or as an easy-pill solution. Most songs, songs that move us, are often inspirational in nature, but I find a lot of inspirational songs are kind of closed to the reality of the sort of work and struggle that goes into ‘being good’. Rather, they want to rely on a more divine causal thing rather than what I’ve experienced in my own life.

I’m writing on my own perspective as someone who’s struggling. I mean like, I was always into Kerouac, I was always into the people that wrote about their own lives, like I believe in that sort of you know, I loved the sort of Beat literature, I love like people–I always just thought that stuff was true. I always loved the idea of the roving gambler in songs. I believe in those mythologies so much, but at the same time, my own mythology is more based on something that I think people can connect with, because I’m actually trying to do something in my songs. It’s not just an accident, you know?

WGO: It brings to mind the song of yours “I Quit My Job”, with the ideas of finding meaning in your own life and rejecting a treadmill existence.

OML: I think that’s probably a pretty good example, and I even quote Woody Guthrie in saying ‘take it easy, but take it’. It’s something that Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger both used to say, but I guess just in some ways we just always want it to be easier for the other guy. We look to entertainment where we want to believe that it’s easy for someone else, and I guess I refute that. I’m just always trying to tell the truth about the difficulties of it all. I think we turn on the television, we listen to music because we–especially if you have aspirations of those things–we think, ‘oh, so-and-so makes it look easy’. But at the same time, I want to make it look easy while explaining how hard it is.

WGO: You mention Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie–I’m reminded of the 1930’s radicals and folksingers of their tradition, and they’re talking about some pretty big ideas in their music. They had a sort of down-to-earth thing while talking about the rise of fascism, the struggles of Labour, racism, some fairly big, concrete challenges that their generation was facing. What are some of the challenges you think our generation faces, big or small?

OML: I don’t know that I’m really qualified to answer that. We’re really individualistic. I was always very antisocial; I always liked people a lot but was never one of the cool kids or picked first for teams. I was always a bit of a loser and I’ve felt like an outsider, so I have a hard time speaking for the group. It’s been interesting that in some ways, singing such individual songs about my own life has been a gateway to finding something that resonates with people.

So it seems to me from where I’m sitting, there are a lot of people who don’t feel like they’re part of the group, everybody feels like they’re kind of on the ‘outside’. Maybe that goes back to what you were thinking earlier about technology. Maybe there is isolation there that is leaving room for someone like myself who is playing a fairly anachronistic instrument at some level, really. And I mean, I don’t believe that, but I can see how one would; that people can find meaning and collectiveness there.

In some ways, it seemed easier for [the 1930’s folksingers] to have those big ideologies. They must have had some horrible fights, and I don’t feel like there’s that same sort of thing [today]. I feel like ‘I Quit My Job’ is such a great song because so many jobs today that aren’t that great, you know? That maybe [people] will have a hard time finding the things that they love, that they want to do and pursue. Then there are of course the big problems that people have.

WGO: Even if you’re hesitant to speak for the “group”, that’s something I do hear a lot, that people are more individualistic, whether that’s good or bad. Maybe it does affect how we consider ourselves as part of the group and whether we consider ourselves as having common challenges.

OML: Yeah, my whole appreciation of the group has come from singing highly individualistic songs. I feel like I was put to it by being an outsider–I guess you probably choose to be an outsider, but I never felt that good about being an outsider. And you know, I still don’t feel like an insider. I do play a weird, ghettoized instrument. I’m not an American artist, not really a folk artist, I don’t spend all my time hanging out with singer songwriters, I’m not an indie artist. I think I just don’t quite know where I fit, and I’m happy that more and more people are okay with that.

WGO: What draws you to that particular instrument, the banjo?

OML: Well, the sound and the rhythm of it. I just find the sound of the banjo really moves something in me, that makes me really kind of crazy, that makes me really excited. There’s a frequency to it that’s great… I just find as a lyricist, [the banjo] kind of lends itself to a certain relationship with language and brevity. The notes are short, and it lends itself to saying what you mean and getting there quickly and moving on, not sort of singing a six-minute song about nothing that leaves people sort of wondering when they can get up and go to the bathroom. It’s good for short attention spans and in some way it’s the perfect modern instrument. Maybe it’s the most modern instrument there is! (laughs)

WGO: I never really thought about banjo in that way!

OML: Neither have I!…but it’s true, it fits my personal aesthetic because I like things that move you, things that make you tap your toe, make you want to sing along, and then maybe where I personally come in is that I like things that reflect a certain view of the world as I would like it to be.

Lynn Rossiter says

We had an opportunity to meet and listen to Old Man Luedecke at Stanfest.

Listened to his CD all the way home. Great music and a humble and intelligent man.

Thanks for the great interview!

Lynn