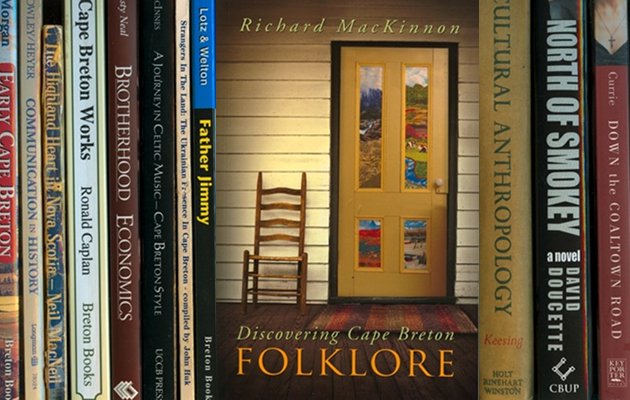

Discovering Cape Breton Folklore

Discovering Cape Breton Folklore

Richard MacKinnon

Cape Breton University Press (2009)

While driving around doing some Christmas shopping in December, I caught part of a conversation CBC Cape Breton Mainstreet host Wendy Bergfeldt was having with Cape Breton University professor Richard MacKinnon. They were talking about the interiors of “company houses” in what was once known as Industrial Cape Breton (back when there was an industry-based economy in the Cape Breton Regional Municipality which, at that time, was known as Sydney, Glace Bay, New Waterford and surrounding areas, but I am on the verge of digressing here) and how people would modify the interiors of these identically-built houses to personalize them, to turn houses into homes.

Having taken Folklore classes from MacKinnon when I went to CBU, (UCCB at the time) I was immediately interested in the conversation and drove past my destination in order to hear more. I found out that they were talking about MacKinnon’s new book, Discovering Cape Breton Folklore and I sat in my car, finally parked outside the Cape Breton Curiosity Shop on Charlotte Street, and listened to the rest of their discussion. Unfortunately they were getting near news time and the end of their chat, but they alluded to some of the other topics discussed in the book including piano playing in the context of Cape Breton’s traditional music, vernacular architecture, and the concept of cultural stereotypes created by outside entities. I realize that may not sound exciting to most people, but these are some of the topics and concepts that I studied at CBU and have been interested in ever since.

So when I got a copy of the book this week, in advance of the official launch taking place today (Friday, February 19) at the Cape Breton Centre for Heritage and Science (also known as The Lyceum) on George Street in Sydney, I was pretty excited to get into it.

Dr. Richard MacKinnon, Professor of Folklore, Problem Centered Studies and Humanities in the School of Arts & Community Studies at Cape Breton University, has been researching Cape Breton’s cultural heritage for more than twenty years. In that time he has had many articles published in respected journals, is the author of Vernacular Architecture in the Codroy Valley, Editor-in-Chief of Material Culture Review, and is Canada Research Chair in Intangible Cultural Heritage, a role which allows him to continue to expand research into various aspects of Cape Breton culture through the Centre for Cape Breton Studies.

To say Richard is passionate about all aspects of the cultural heritage of Cape Breton Island would be to define understatement. It was this passion that piqued my interest in topics like “vernacular architecture” beyond the yawn-inducing sound of the subject itself. In class, MacKinnon early on made the connection between what the people who came before us did with their day-to-day lives and what impact that has had on the way we live our lives today; how the culture of Cape Breton has been shaped in its most basic sense, by how generations before us have lived their lives. Folklore, in that sense, is like a history of the people, by the people, made when no one was looking; it was just people living their lives. And that is what is so interesting about this book.

A musician himself, MacKinnon opens Discovering Cape Breton Folklore with three chapters about music in Cape Breton—Cape Breton Folksong Collecting; The Dynamics of Cape Breton Piano Style; and Protest Song and Verse in Cape Breton. These chapters tell us about music in Cape Breton in a different context than usual. In describing the details of song collecting, piano styles and the composition and spreading of protest songs, MacKinnon tells not only of the role music played in the lives of the people of these times, but of these people and these times themselves.

And this is the story told all through the book. With chapters on humourous nicknames and cockfighting, the reader gets an unexpected sense of what life was like for the hard-working folks of Industrial Cape Breton; chapters on log architecture, company housing, and the Cooperative Movement in Tompkinsville shed light on the lives of the people who settled in Cape Breton and worked to make their place here. Each chapter offers fresh insight into subjects that have been covered before, and there are suggestions throughout for areas that would benefit from further research.

The final chapter, Public Image and Private Reality in Cape Breton Folk Traditions, offers a perspective on Cape Breton culture that I think is much overlooked, if ever even acknowledged at all. It is about how culture can be created by outside forces to be used for purposes like promoting tourism, thereby corrupting the very history of a place and people and leading to the kind of stereotypes which, if consumed unknowingly, eventually destroy the culture they were created to represent.

Discovering Cape Breton Folklore is an interesting read for anyone who is interested in Cape Breton culture. In a very real sense, it is a history of Cape Breton told by people who lived here when they thought nobody was listening. First person accounts of events, photos, diagrams, and appendices, along with fourteen pages of references in one of the smallest fonts I’ve seen outside of a footnote, make this a very informative book. MacKinnon’s approach to, and presentation of the material kept me interested and made me want to know more. Maybe I’ll start in on that list of references to pick the next book I read.