Somebody has smashed out the brains of “Wee Thomas”, the beloved cat of Padraic, the most feared, violently psychopathic campaigner for the liberation of the island of Ireland from British domination (Padriac is so demented even the Irish Republican Army steers clear of him).

Donny, Padriac’s father and custodian of “Wee Thomas” while his son is off trying to blow up fish and chip shops for the cause, believes Davey, of the long flowing, girlish locks, did the deed while recklessly racing his Ma’s borrowed bicycle. Davey, protests his innocence of the cat-icide, especially given Padriac’s murderous ways and his close bond with “Wee Thomas”.

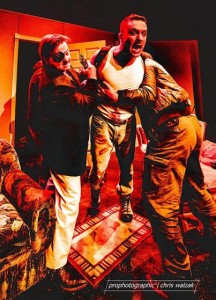

Padriac receives the news while holding a straight razor to the nipple of a drug dealer for selling pot to Catholic schoolchildren (Padriac is just fine with selling pot to Protestant schoolkids). Donny tries to soften the blow by telling Padriac that “Wee Thomas” is feeling poorly. Padriac does not take that news well and hurries back to his home village of Inishmore to check on the health of his cat.

After that, Martin McDonagh’s black comedy, The Lieutenant of Inishmore, features an escalating body count of felines and felons as the characters trade insults and debate the finer points of terrorism, such as the morality of shooting the eyes out of cows for political change (“Who would want to eat a blind cow?” is a premise that has almost universal support) and the role of cat assassinations in creating a free Ireland.

McDonagh’s plays are famous for their dark humour and his take no prisoners depictions of life in his native Ireland: he’s unafraid to serve humour from any number of sacred cows—eyeless or otherwise. His movie, In Bruges, about two hapless hitmen exiled to the Flemish tourist town, is probably the most typical and widely known example of his work as the Celtic Tarantino.

The Highland Arts Theatre’s production of Inishmore enthusiastically plunges into McDonagh’s bloody excess and delivers a short sharp shot of ferocious hilarity.

Director Kristen Gregor keeps a lickety-split pace to the almost cartoonish violent going’s on. This play had some of the quickest and most deft scene changes I had seen which is especially important to keep the audience from dwelling on what might objectively be called a horrific amount of violence. She also brought strong work from her cast, especially the several newcomers. She managed the difficult physical effects well: guns fire, blood spilt, and cats, alive and otherwise, are centerstage. Any of these things mishandled could have seriously tripped up the production, but Gregor and her stage crew flawlessly handled them.

Jenna Lahey, as Mairead, Davey’s cow-blinding teenage sister who still moons over Padriac and his rebel ways, also brought a fierce physicality to her character that underscored her always argumentative dialogue. This is also her third appearance in a play in a little under a month which makes her as mad as her character.

As a trio of “splinter sect” gunmen after Padriac, Sam White (Christy), Clayton D’Orsay (Joey), and John-Paul Bergeron (Brendan) were another great comedy team. White gave Christy a welcome outsized dollop of the ole’ Blarney, relishing every nonsensical bit of dialogue his character spouts. D’Orsay and Bergeron were visual opposites (smart casting by director Gregor) and also delivered their quarrelsome lines with a droll offhandedness (although with MacNeil, their relative inexperience showed in terms of occasional low volume and some problems with clarity in pronunciation).

And how can anybody not love a play featuring a scene where the always excellent Daniel Dobson is tortured onstage? His moments of painted defiance and desperate pleading are on their own worth admission.

A couple of innovations in presentation are worth noting: the play has a relatively late start time of 9 pm, following each performance a local band performs–Rad & Subtract, The Full Effect, and Analog Signal have already played with Black Tooth Grin and Static In Action scheduled for Wednesday and Thursday–and because beer is served admission is restricted to those of legal drinking age.

I don’t know if the inclusion of a black cat makes The Lieutenant of Inishmore a Halloween play, but it is uproariously funny enough to enjoy any month of the year.